Researching the politics of development

Blog

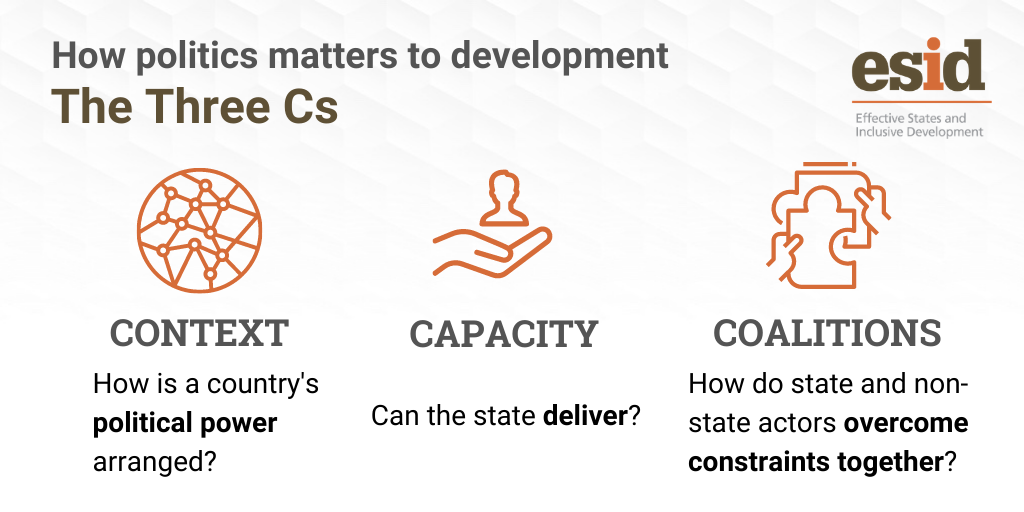

The Three Cs of inclusive development: Context, capacity and coalitions

30 September 2020

Sam Hickey and Tim Kelsall set out the ESID framework for inclusive development.

When ESID started its work in 2011, it had become widely accepted within international development that politics mattered. What was less clear was the specific ways in which it mattered and which forms of politics drove which forms of development.

It was clear that one-sized approaches that promoted best-practice irrespective of contextual differences weren’t working, and that politics was a central part of this puzzle. However, how we should understand these political obstacles to development or identify the political drivers was less apparent

At ESID, we posit that there are three crucial areas to look at in a country that will give you a good start in understanding what’s going on and what might be worthwhile entry points: ‘Context’, ‘Capacity’ and ‘Coalitions’.

These are our ‘Three Cs’ of inclusive development. They aren’t the only thing to look at, of course, but they provide a good starting point. It’s critical to appreciate the interplay between these ‘Three Cs’ to get a clearer picture of why and how development progresses in different ways in different places. In this blog, we will explain them in more detail, with some short examples.

Context: How is a country’s political power arranged?

ESID understands political context through the idea of the political settlement, which describes the balance of power and rules of the political game in a particular place. Studying the local political context can help identify the different pathways through which development occurs.

It’s not that one political settlement is better than another; it’s important to note that different settlements can achieve the same development outcomes. But countries with different settlements are likely to achieve similar outcomes via different routes.

One example from our work is a comparison of how Ghana and Uganda managed the discovery and extraction of oil reserves in their respective territories. This was influenced by their respective political settlement.

These two countries had similar sized oil discoveries and negotiated with similar international oil companies to make deals on the state’s cut of oil revenue. Uganda took a long-term view and negotiated hard with international oil companies, whereas Ghana rushed into less regulated deals. As a result, Ghana moved more quickly to oil extraction and revenues, but with a smaller share of state revenue, while Uganda received much better deals on paper but has moved very slowly in terms of actual production.

Political settlement analysis can help explain why each country moved in a different direction. A “dominant” political settlement in Uganda enabled a longer-term perspective from the government, whereas the more competitive political settlement in Ghana encouraged a shorter-term perspective. Ideas also mattered: Uganda’s governing elites are ideologically aligned to a more ‘resource nationalist’ approach to oil governance, as compared to the more neoliberal tendency that prevails in Ghanaian politics.

Capacity: Can the state deliver?

States are ultimately responsible for the welfare of their citizens. No other form of public authority has emerged that is capable of negotiating with international capital, or providing security and other public goods to citizens at scale.

In the past, the good governance agenda in development had focused on good democracy and institutions as being the key to development, but state capacity needs to be taken seriously too. Before they can be held accountable, states first need to be capable of developing and delivering policies. As Goal 16 of the SDGs asserts, developing countries need institutions to be effective as well as inclusive.

In our research, we show that state capacity is important for inclusive development, but that it varies between countries and also within countries, both in terms of different policy domains and different parts of the country. At the national level, state capacity is directly linked to achieving higher levels of poverty reduction and development at a national level. For example, countries with higher levels of state capacity achieved much better progress towards meeting the Millennium Development Goals from 2000 to 2015.

Second, what enables countries to achieve some policy objectives but not others often depends on whether bureaucratic ‘pockets of effectiveness’ have been offered the autonomy and capacity to deliver in a given policy domain.

Here our research shows that such pockets can be critical for delivering economic stability but offer less promise for social sectors. We find that the capacity of states to deliver varies considerably across national territories, with some districts performing much better than others. In all cases, whether or not national or local governments actually build and deploy state capacity to deliver development is directly shaped by the political settlement.

Coalitions: How do state and non-state actors overcome constraints together?

Our final C is coalitions. We have found coalitions to be a key mechanism through which the choppy waters of political settlements can be navigated.

Most political settlements fail to generate incentives for elites to come together and deliver equitable improvements to society. In situations like these, positive change for the underrepresented is often catalysed by individuals and groups coming together in coalitions to wrestle with the structural barriers to action and progress.

These coalitions are formed of a combination of politically salient actors: politicians, bureaucrats, business leaders, social movements, religious groups, regional authorities, epistemic communities and international donors. We often see coalitions forming to advocate for political reform and working together to overcome obstacles, coming up with new ideas and finding new ways to push progressive policies and legislation through.

ESID researcher is illustrative of how coalitions can be a key driver in creating social change. Across Bangladesh, India, Rwanda, Ghana, South Africa and Uganda, anti-domestic violence policy coalitions were important actors in pushing new laws through parliament.

Women’s movements formed alliances with other actors (bureaucrats, politicians, religious leaders, etc.) to make the case for this legislation within the context of dominant ideas and incentives within the national political settlement.

Importantly, the types of coalition required to achieve success was different in different political settlements. Confronted with a dominant political settlement, the key for women’s movements in Rwanda and Uganda was to make the case for anti-domestic violence legislation in ways that resonated with the ideas and incentives of the president. In the competitive clientelist context of Bangladesh during the late 2000s, women’s activists struggled to forge programmatic links with either of the two main parties and instead relied on alliances with senior ‘femocrats’ and on the Prime Minister’s national pride when it came to alignment with UN-level commitments.

Through our comparative research across different political settlements and policy domains, we have sought to go beyond the mantra that politics matters to development, to show the particular ways in which it matters. With these insights, we hope to help suggest how practitioners might adopt different ways of working in different political contexts, and of supporting both the capacity of states and the coalitions required to deliver inclusive development.

We are currently synthesising ESID findings from ten years of research. Look out for lots more exciting blogs, videos, animations and more on our key findings in the next few weeks.