Researching the politics of development

Blog

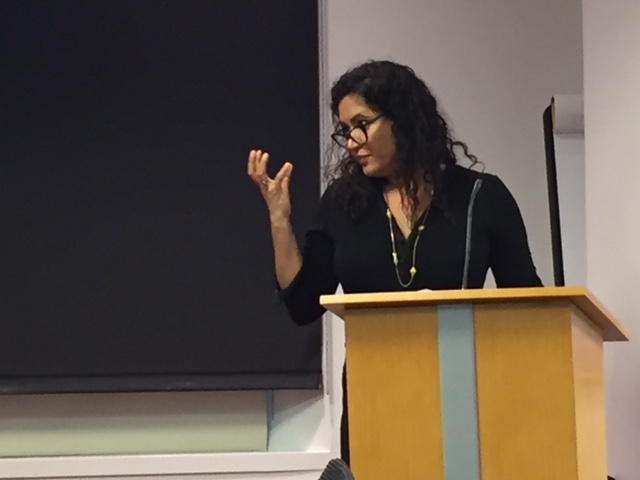

Spotlight on an ESID expert – Naomi Hossain

11 May 2017

ESID and IDS researcher Naomi Hossain on her passion for development research, linking climate change and development and moving house for the eigth time in 12 years…

1. What made you want to work in development research?

I was brought up in Bangladesh and the world of aid and development was always very familiar. Then at university I was very involved in feminist and queer politics and other social justice issues, so it was a quick and easy step into development when I left. My first job was at BRAC in Bangladesh, my second at the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex, my third at BRAC again and my fourth and current at IDS again.

2. What’s the current focus of your research?

I’m currently fascinated by the long-term effects of famines and disasters on the politics of development. On whose crises count, the significance of memories of major disasters and how elites politicise and use them, and their effects on popular political culture. I’ve done a lot of work on the recent global food crisis that has so far been unconnected to my work at ESID. But I’m trying to bring these parts of work closer together, by looking at the political effects of the food/fuel/financial crisis of 2008 on the drive for social protection in development. If Kunal and Sam let me.

3. What do you think are the most important findings from your work with ESID?

That competitive and dominant political systems both encourage bigger – but not necessarily better – education systems. Development is itself part of the political process that drives quality up: the nature of school systems means that parents and communities must play a big role in monitoring them and holding them to account over quality – no bureaucracy or technocratic solution can do that. But parents and communities must know what to expect and how to demand it, and that only really comes with a certain amount of material security and human development. I also think we are finding that business elite interests in higher average skills in the mass population probably drives demand for higher quality education, but we have no actual evidence on the mechanisms of how that works yet. Something for the next research project…

4. What are the greatest challenges currently facing the development sector?

Climate change and conflict, which is increasingly looking like the same thing. A decade ago, we were talking about famine as largely a historical phenomenon. In 2017 there is a very good chance that tens of millions of people will face starvation. For them, development has been an utter and literal disaster.

5. What is one change you most want to see happen in development?

For rich countries to stop acting as though they were doing everyone else a favour when they make their ODA allocations, recognise that it is recompense for climate change and empire, and explain to their own citizens that aid is in their interests more than anyone else’s. Or is that three?

6. Tell us a little about your life and how you spend your spare time

We’re just about to move to our 8th home since my daughter was born 12 years ago, so I guess relocating is what I do in my spare time. IDS have very generously let me telecommute for the last 6 years so I travel quite a bit to and for work. But home is Washington DC currently, which is good for modern art, modern American cuisine, and protests – all of which I like a lot.

Read Naomi’s research on education quality in Bangladesh.